UC Davis Admissions Dean Discusses Ways to Continue DEI Despite Legal Obstacles

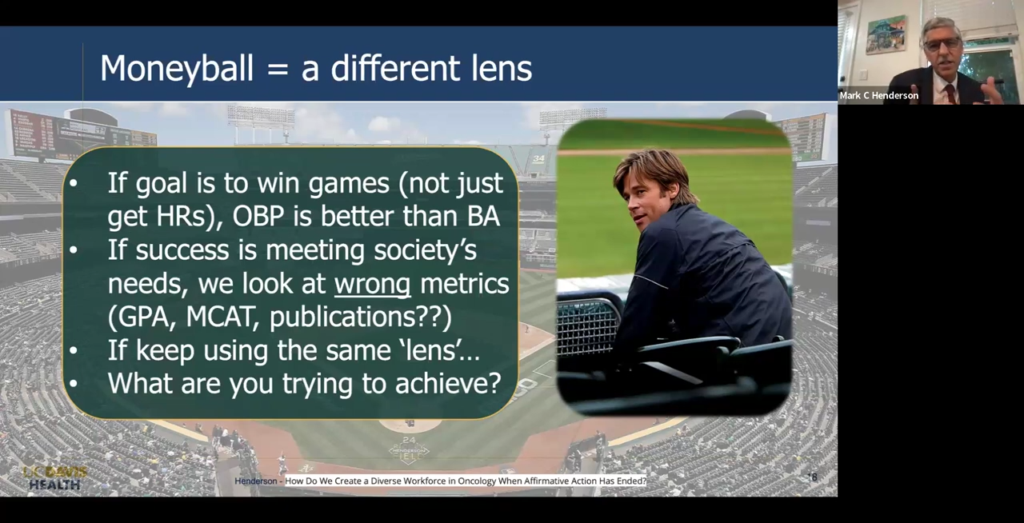

“If success means meeting society’s needs, we’re probably looking at the wrong measures at this point […]: grade point average, MCAT, publications. There’s not a lot of evidence that those measures actually improve health outcomes in society.”

Those are the words of Mark Henderson, MD, the Associate Dean for Admissions at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine. Henderson made the comments at an October 2024 grand rounds session hosted by Stanford Medicine’s Obstetrics and Gynecology department titled “Cultivating Physicians Our Nation Needs After Affirmative Action Ended.”

There, Henderson discussed ways that medical schools and graduate medical education programs could continue to engage in diversity initiatives and discriminatory practices in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which found race-conscious admissions to be unconstitutional.

A key point: Henderson’s comments are particularly noteworthy as California has banned race-conscious admissions for decades, and yet UC Davis has succeeded in diversifying its student body through its “socially accountable” admissions practices (more on that later).

One doesn’t need to read between the lines of Henderson’s comments: he is explicitly calling for schools to devalue objective metrics of academic achievement like GPA and MCAT scores in favor of criteria that favor qualities such as diversity. As Henderson later says, the mission of UC Davis Medical School is to “matriculate future physicians who will address the diverse health workforce needs of our region.”

Of course, Henderson’s premise is just not true; MCAT scores, for example, are predictive of performance on Step 1 and Step 2 of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam or USMLE, which is in turn predictive of clinical performance.

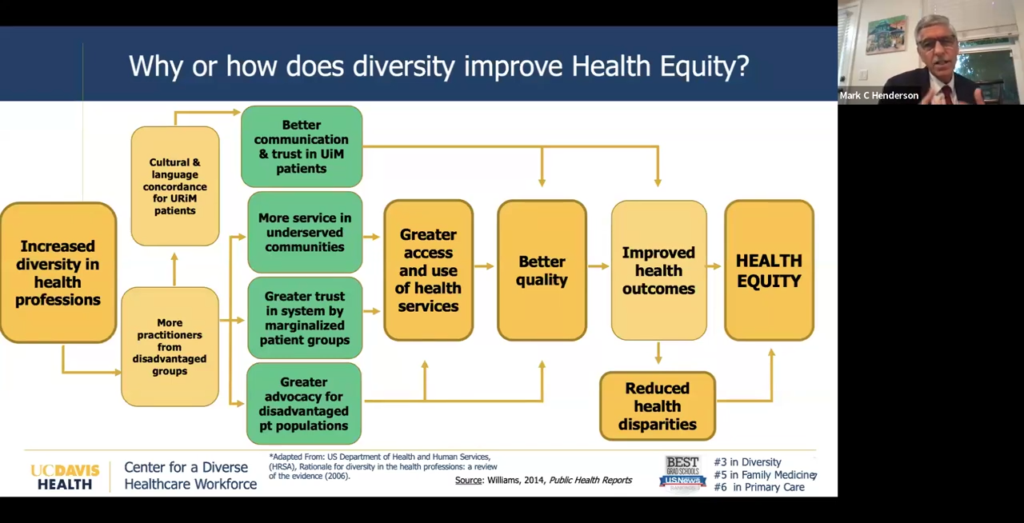

To justify this DEI-centric approach to admissions, Henderson makes the argument that a diverse healthcare workforce actually leads to better health outcomes for patients.

Henderson, without explicitly using the words “racial concordance,” alludes to the notion that patients (particularly patients belonging to racial minorities) will experience better health outcomes when treated by physicians of the same race.

As Do No Harm has repeatedly shown, this argument, commonly employed to justify discriminatory diversity hiring practices in healthcare, is bunk. Five out of six systematic reviews find that racial concordance has no impact on health outcomes.

That hasn’t stopped Henderson and co., of course. Indeed, UC Davis tied for the lowest marks in the Center for Accountability in Medicine’s Medical School Excellence Index, which assesses medical schools on their commitment to academic achievement and merit over radical ideology.

To achieve its diversity goals, Henderson touted UC Davis’s “socially accountable” admissions strategy, which aims to deemphasize measures of academic achievement in favor of measures that appear to be proxies for diversity.

This behavior isn’t new from Henderson and UC Davis: Do No Harm previously reported on a 2022 webinar in which Henderson, discussing UC Davis’s admissions process, stated that the “overrepresentation” of Asian physicians is addressed through an “institutional diversity and inclusion policy that explicitly and publicly states our priorities for recruitment based on the statistical gap between California’s population and the physician workforce demographic of underrepresented groups.”

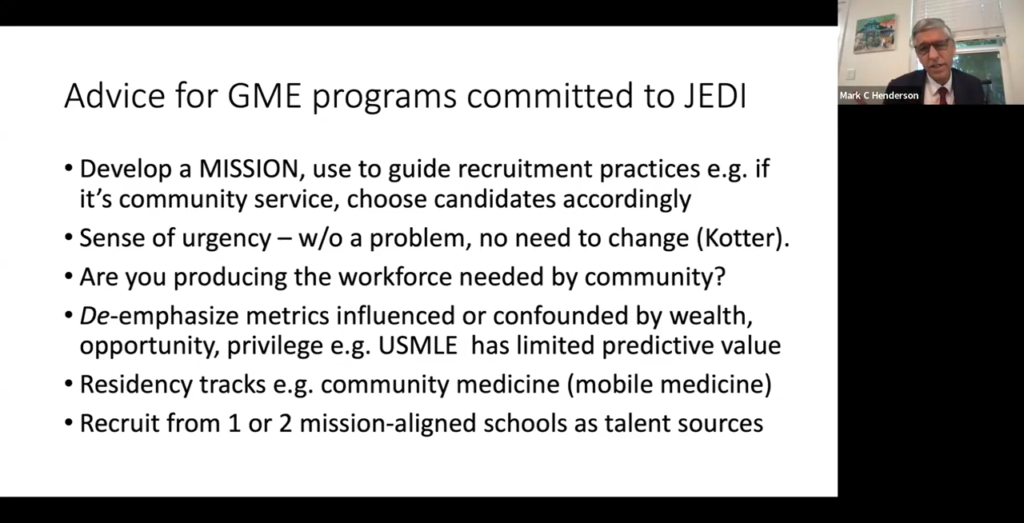

Next, Henderson took care to stress that the Supreme Court’s decision did not apply to graduate medical programs, such as residency programs, and encouraged them to continue to engage in diversity initiatives consistent with local laws and federal civil rights law.

Again, Henderson encouraged programs to de-emphasize metrics of academic achievement, which Henderson characterized as being “confounded” by wealth and “privilege.”

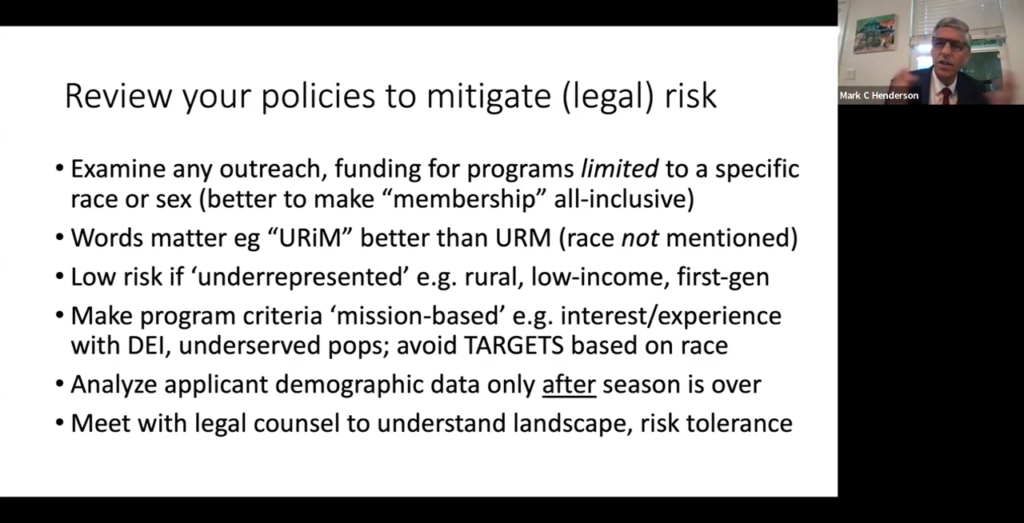

Next, Henderson offered ways for programs to mitigate their legal risk by cloaking DEI initiatives in terms that may obscure their racial focus.

“Words matter. ‘Underrepresented in medicine’ is a term that means that the population, whatever the identity is, is underrepresented relative to the population,” Henderson said. “That’s better than ‘underrepresented minority,’ which refers to racial identity.”

And finally, Henderson concluded by encouraging residency program directors to balance the legal risk of discriminatory practices and policies with the goals of diversity.

“Try to light some fires,” he said, urging residency programs to follow their (DEI-centric) missions.

Well, there is one surefire way to mitigate risk: stop engaging in discriminatory diversity initiatives that treat individuals on the basis of their race, rather than their merit.

Unfortunately, this seems to be a bridge too far for Henderson and UC Davis.