Commentary

Lies, damn lies, and statisticians: A transgender paper that fails the test

Share:

Economist Ronald Coase observed that “if you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything.” A paper recently published in PLOS One devised some particularly creative means for extracting a confession.

The authors of “Anti-transgender rights legislation and internet searches pertaining to depression and suicide” claim to observe “that the passage of a single [anti-trans] bill led to around a 13 to 17 percent increase in the volume of searchers for the word ‘suicide’ within that state.” Moreover, they said “that for every anti-transgender bill passed in a week, there was about a five percent increase in searches for the word ‘depression.’” They assert that the increased interest in these terms reflects increased mental health distress, brought on by legislation.

The researchers derive their conclusion from multiple regression analysis, a technique used to observe the relationship between a dependent variable (searches for “suicide” and “depression”) and multiple independent variables (the status and timing of “anti-trans” bills). Google searches constantly fluctuate for a variety of reasons, so simply observing whether searches increase or decrease in the wake of new legislation would not sufficiently address the researchers’ question. Indeed, sophisticated analysis is required to attempt to isolate the potential effect of new legislation on internet searches.

While sophisticated quantitative methods are useful tools for serious scholars who pursue truth, they can also be used by activist scholars to create the aura of “science.” It is easy to deceive readers who are uninitiated to the nuances of quantitative methods. And sure enough, a technical deep dive of the PLOS One paper reveals that its methods are flawed on their merits, rendering the conclusion invalid.

Only a limited number of health policy scholars have the statistical skillset required to interrogate the paper’s approach, including, perhaps the peer reviewers and editors at PLOS One. But even reviewers or editors not well-versed in statistical methods should assess whether a research paper passes a face validity test. The extent to which this new paper fails that test is staggering, which makes its publication particularly disconcerting.

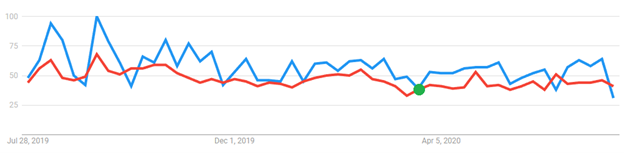

The relationship between two phenomena (i.e., the timing of “anti-trans” bills and Google searches for “suicide” and “depression”) can only be observed to the extent that the items vary. It would be impossible, for example, to estimate the effect of sunlight on plant growth if it was cloudy or sunny 100% of the time. Herein lies a major issue with their dataset: Only two “anti-trans” bills were passed within their study time horizon, and both were in Idaho on the week of March 22, 2020. Given this limitation, face validity demands strong evidence that the bills in Idaho were in fact associated with an increase in searches for “suicide” and “depression.” At the very least, unsophisticated examination should track with their conclusion to verify that it isn’t simply derived from tortured data. Instead, Google Trends indicates that the adjusted number of searches in Idaho that week for the word “suicide” (derived by taking the frequency of a specific search term, dividing it by the total number of Google searches and then normalizing the results relative to a peak of 100) was below average for Idaho compared to the year overall, and aligned with national trends.

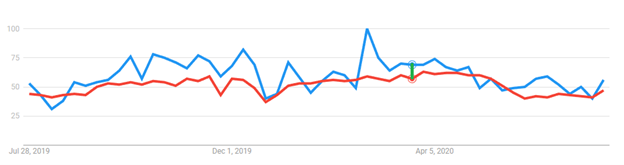

Searches for “depression” in Idaho were also consistent with national data, and just slightly above the state average for the year.

Put simply, the single data point that allows the researchers to make an inferential analysis tells a different story from the conclusion they attempt to torture from it.

It’s bad enough that the variables don’t have the relationship the authors try to impose upon them. But it should also be noted that the timing of the Idaho bills’ passage casts serious doubt about the wisdom of empirical analysis. The week of March 22, 2020 coincided with the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, which dominated news headlines and disrupted nearly all facets of life. “Anti-trans” bills can only provoke feelings of suicide or depression if individuals are aware of and thinking about such bills. Amidst a historic, spiraling public health emergency, would legislation that prohibits gender changes on birth certificates or forbids biological men from competing in girls’ sports have wide resonance with Idahoans? One should be skeptical.

Finally, even if the legislation was associated with an increase in searches for the terms “suicide” and depression” (it wasn’t), and even if Idahoans were in fact mindful of the new legislation (a questionable proposition), there’s another problem. Someone who prioritizes empirical rigor might wonder whether the search results are, in fact, a proxy for mental health distress, or whether they are an artifact of media coverage of the legislation. Transgender activists and their allies in the academy and media repeatedly make the erroneous claim that their policy objectives would curtail the high incidence of depression and suicide in trans-identifying youth. Consequently, it’s plausible that Google searches for “suicide” and “depression” increase in response to media-driven interest in the topic, not mental health distress. The authors never address this possibility nor attempt to disentangle it in their analysis.

Whether this paper was produced out of sloppiness or an attempt to advance a cultural objective is unknown, but the effect is all the same: More junk science obfuscates rather than informs debates around gender topics.