Commentary

The Most Pressing Issue in Family Medicine Is…Climate Change?

Share:

The last thing you would expect to see after opening up a medical journal is a deluge of articles about the “climate crisis”. Yet, that’s exactly what is contained in the latest volume of the journal of the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM).

Roughly 35 percent of the 26 articles contained in the most recent email to ABFM members detailing their journal’s table of contents are principally about climate change or the environment. These include commentary pieces, original research, the editors’ note, and more. Pieces such as “Climate Change: How Will Family Physicians Rise to the Challenge?” and “When Climate Change Shows Up in the Exam Room” nearly outnumber articles about conventional medical conditions or research.

For certain subcategories of research products, the climate-theme is even more overwhelming. For example, five out of the six commentary pieces in the latest addition of the journal pertain to climate change; the one non-climate change commentary piece is entitled “Lack of Diversity in Female Family Physicians Performing Women’s Health Procedures.”

The overwhelming argument contained in these research products is that climate change is discussed too little in family medicine (which somewhat ironic considering the sheer number of pieces dedicated to the topic), yet is of the utmost importance.

For example, in “Climate Change: How Will Family Physicians Rise to the Challenge?”, Audrey Hertenstein Perez argues that much more needs to be done in immersing physicians with the climate change agenda. She states: “There is an emerging field of Climate Health with fellowship training programs and residency curriculums available for collaboration. We must make this education a standard part of medical school and residency training to ensure that future physicians are adept to address climate change both within an office encounter and the communities in which they practice.” She goes onto condemn much of the medical field in her claim that “Hospitals and clinics rely heavily on fossil fuel-based energy and each laboratory test, imaging study, and pharmaceutical intervention increases this intensive energy demand.” The solution, according to Perez, is for doctors to become climate activists: “We also have a powerful voice as advocates. We must use that voice to approach local or national legislators to support measures that will mitigate climate change while assisting communities to adapt to the changes already at hand.”

Mona Sarfaty echoes some of these sentiments in “How Physicians Should Respond to Climate Change” by calling for climate change to be incorporated into medical education, stating “Medical schools should waste no more time in ensuring that medical education is up to date about climate change.”

In “Climate Change Psychological Distress: An Underdiagnosed Cause of Mental Health Disturbances”, Jessica de Jarnette details the symptoms of “Climate change psychological distress (CCPD), also known as climate anxiety” which is “a chronic fear of environmental doom…ranging from mild stress to clinical disorders like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide.” The evidence cited by de Jarnette for this so-called crisis in family medicine is simply a handful of cherrypicked public opinion polls of Americans indicating they are worried about climate change. Meanwhile, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) ranks the most prevalent mental health conditions in the United States— “Climate Change Psychological Distress” is nowhere to be found on their list.

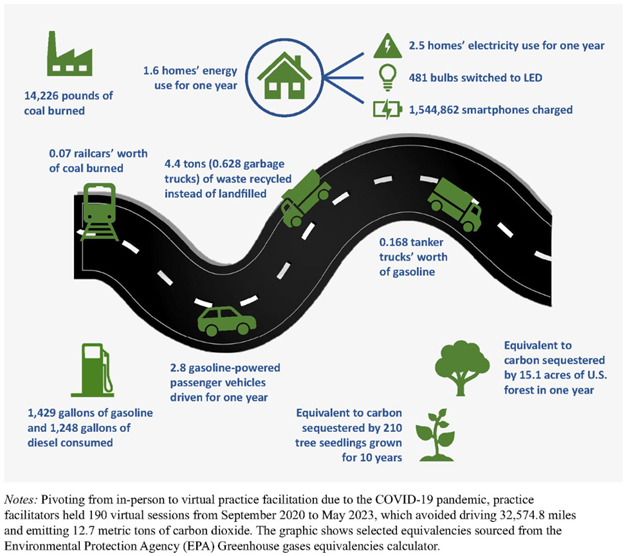

In “Considering the Environmental Impact of Practice-Based Research”, several authors decry the “carbon footprint” generated by “the need to commute by automobile to and from [medical] practices” for practice-based research. The authors suggest virtual practices, e.g. telemedicine, are a necessary solution. While there are many virtues of telemedicine, the authors conveniently make no mention of the countless patients who may be one of the 42 million Americans without access to broadband. Are these patients to forgo their medical care for the sake of reducing carbon emissions?

Put simply, the general theme of these pieces is quite similar: climate change is bad. Medical schools must incorporate the climate agenda into their curriculum. Doctors must become climate advocates both inside and outside of the exam room. Carbon emissions must be reduced. And repeat.

This is hardly the first instance of activists attempting to use family medicine as a means to promote a social or political agenda. As Dr. Goldfarb pointed out roughly two years ago, “When someone walks out there with their white coat on and their stethoscope and starts talking to you about the dangers of climate change, that changes the discussion about climate change. And I think that’s really been the motivation to try to generate more social activity on the part of physicians.”

At this pace, it will be refreshing to stumble upon articles in medical journals that actually pertain to legitimate discussions of medical issues, ethics, and research. However, if current trends continue, these types of articles may become the exception rather than the rule.