Commentary

UMass Chan Medical School Imposes Identity Politics on Faculty, Polices Language

Share:

At the UMass Chan Medical School, “inclusive” seems to have a concerning meaning.

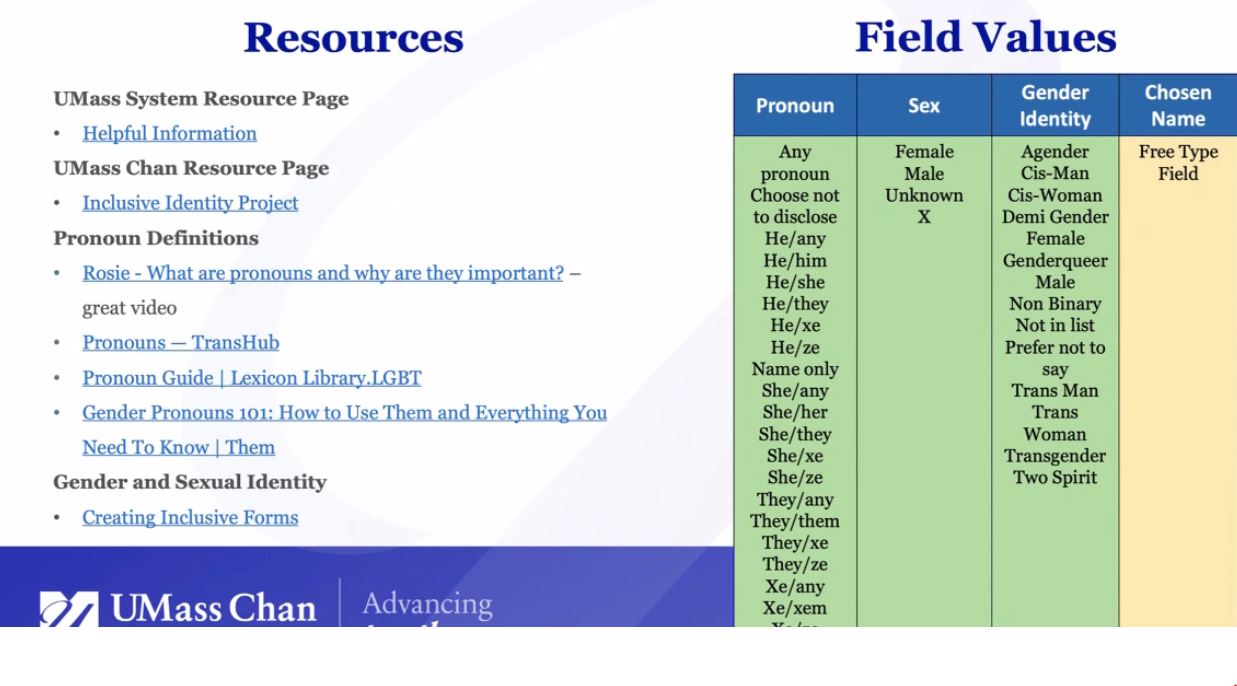

One of the school’s programs, the “Inclusive Identity Project” sponsored by the school’s Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, enables faculty members to select their own pronouns in the school’s human resource system and mark their sex as “X.”

“Recognizing that sex is not a binary, nearly half of U.S. states, including Massachusetts, allow individuals to have an X on their birth certificates and/or driver’s licenses to indicate that they identify as a sex other than female or male,” the school’s Inclusive Identity web page states. “Enabling UMass employees to have an X as their sex respects the diversity of our society and is in keeping with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts offering X as a legal sex on driver’s licenses.”

The program also encourages faculty members to use individuals’ preferred pronouns and “gender identity” nomenclature.

“The best thing to do if you realize you just used the wrong pronoun for someone in a conversation with them is to say something right away, such as ‘Sorry, I meant they,’” the FAQ reads. “Fix it, but do not call special attention to the error. If you realize your mistake after the fact, apologize to the person at your next opportunity. Please do not go on and on to the misgendered person about how bad you feel that you made that mistake or how hard it is for you to get it right.”

Other initiatives promoted by the school diversity office include racial and sex-oriented “affinity groups.”

For instance, the “People of Color Affinity Group” aims to “create a safe space where those who have experienced structural oppression, marginalization and/or other microaggressions can share their experiences with others who have a shared sense of identity.”

As another example, the “AALANA” affinity group “represents African American, Latinx, Asian and Native Americans” and “seeks to support and advance faculty of color through collaboration, celebration, and knowledge.”

Do No Harm is no stranger to UMass’s concerning vision of inclusivity; in 2023, Do No Harm filed a complaint with the Department of Education Office for Civil Rights over the school’s Pipeline for underrepresented Students in Medicine (PRISM) program, which included discriminatory eligibility criteria.

The previous eligibility criteria stated that applicants “must be a member of historically underrepresented groups in medicine e.g., Blacks, Mexican Americans, Native American (American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians), and of Hispanic origin.”

The current eligibility criteria for the PRISM program state that “Individuals historically underrepresented in STEM, health science and medicine are strongly encouraged to apply,” and that “[p]riority will be given to students that identify from one of the following underrepresented groups in STEM, health science and medicine: Black/African Americans, Hispanic or Latinx, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islanders.”

Then there’s the UMass Chan Medical School Summer Learning Opportunity (SLO) program.

[The p]rimary goal of this program is to increase representation of men of color, particularly Black men[,]into medicine. All students are welcome to apply[.] Priority will be given to URiM,” the program description states.

“The AAMC defines URiM students as ‘those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population … which includes African Americans, Hispanics/Latinx, American Indians, Alaska Natives, native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders,’” the description continues.

To be clear, these individuals are not underrepresented as a percentage of qualified applicants, only as a percentage of individuals in the population. Qualified individuals who are members of these racial groups are readily accepted to medical school and numbers out of proportion to their academic performance as undergraduates and on MCAT exams

It’s clear that for UMass Medical School, “inclusivity” is often a proxy for radical ideology and identity politics that treat people less as individuals and more as members of specific groups.

Needless to say, this is not conducive to effective medical education. Individuals should be viewed through the lens of their achievement and merit, and not their group identity.