Commentary

University of Texas Medical Branch ‘Study’ Hints That the School Remains Fixated on Race

Share:

DEI activists insist that racial/ethnic group differences in academic readiness for medical school or performance in medical school must be evidence of racist systems. In response to this imagined racism, they demand reform that obfuscates differentiation in performance. So, for example, “holistic admissions” tone down the once-prominent role of MCAT scores and GPA in determining medical school admission in favor of fuzzy personal attributes, like the candidate’s commitment to the school’s mission.

Because “underrepresented” (i.e. black or Hispanic) applicants tend to have significantly lower GPAs and MCAT scores than white and Asian applicants, this enables medical schools to continue advancing their diversity goals with plausible deniability that they are engaging in racial discrimination.

The latest absurdity comes from University of Texas Medical Branch researchers publishing in the journal Advances in Medical Education and Practice. The study supposedly “aims to compare traditional admissions interviews with Multiple Mini Interviews [i.e. 7 to 9 short interviews instead of one long one] to assess their reliability in evaluating applicants across racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.” The data for this study comes from the University of Texas Medical Branch John Sealy School of Medicine (JSSOM), which changed its interview format to mini interviews in 2022 after the “admissions committee observed inconsistencies in interview scoring, topics discussed during interviews, and interviewer comments using an unstructured interview format.”

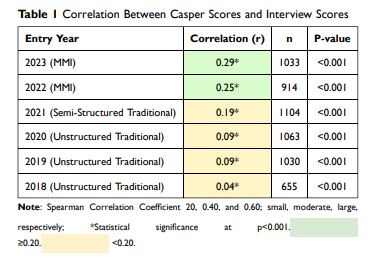

The “study” involves two separate analyses. In the first part, the researchers observe the correlation between interview scores and Casper scores according to interview type. “The Altus Assessments Casper test is an online situational judgment test designed to evaluate an applicant’s noncognitive skills, including ethical judgment, communication, and professionalism.” The correlation between interview score and Casper score improves from essentially non-existent to small when the school adopts multiple mini interviews.

At face value, this would seem to speak well to the multiple mini interviews format. In reality, however, there is no test that can accurately assess “an applicant’s noncognitive skills, including ethical judgment, communication, and professionalism.” Were that so, all employers would be administering these tests to prospective employees. Instead, these types of skills are appraised as a matter of human judgement. In the case of medical school, it’s likely that they are best evaluated through long interviews that test a candidate’s endurance and limit their ability to offer scripted answers. In other words, the multiple mini interview format is a solution in search of a problem.

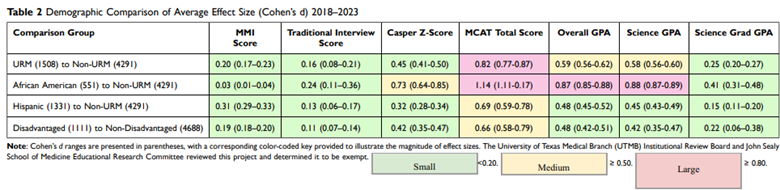

In the second part of the analysis, the researchers assess whether using the multiple mini interview format reduces ethnic and economic group differences in interview score. They observed that multiple mini interviews “reduced differences compared with traditional interviews for African American candidates and slightly increased differences for URM, Hispanic, and disadvantaged candidates.” Of course, group differences in interview scores are no more evidence of discrimination than differences in MCAT scores, but the researchers don’t entertain that reality and favor an orthodoxy that differences must be evidence of discrimination.

In a particularly revealing display of their motives, the researchers show group differences in MCAT scores and GPAs but provide the information in a convoluted way that makes it impossible for the reader to discern which groups perform higher.

Again, generally speaking, applicants from groups “underrepresented in medicine” (i.e. Hispanic and black) have significantly lower GPAs and MCAT scores than white and Asian applicants and face lower admissions standards. Acknowledgement of this fact is made all but impossible by their rationalization that multiple mini interviews allow “for a more granular and specific evaluation of candidate abilities, improving the precision of scoring by reducing subjectivity and enhancing reliability in assessing key competencies.” A test like the MCAT is the gold standard when it comes to “objectivity.” Were that indeed their primary concern, they would conclude that, on average, candidate quality does in fact vary by ethnic group.

Ultimately, it’s unclear whether multiple mini interviews facilitate skirting the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative action. What is clear, however, is that tinkering with the admissions process at JSSOM is occurring in service of racial consciousness. As the researchers themselves acknowledge, “Finding a way to assess the interpersonal and intrapersonal characteristics of applicants accurately is critical given the recent Supreme Court decisions in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. (SFFA) v. University of North Carolina and SFFA v. President & Fellows of Harvard College.”

JSSOM, like all schools, should be focused on attracting the beat and brightest candidates. This study should invite healthy skepticism regarding the school’s commitment to that principle.