Medical School Hosts Presentation Dismissing Adverse Health Consequences of Obesity

It might seem obvious that a medical school should teach students pertinent medical information, not promote ideological programming that downplays genuine health concerns.

The Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, however, appears to disagree.

This February, the school hosted a presentation that encourages acceptance of obesity and seems to dismiss the serious health risks associated with excess weight.

The presentation, which was offered during the school’s “Doctoring 1” class for first-year medical students, downplays the health risks of obesity and instead paints the focus on such risks as evidence of stigma, bias, and even racism.

First, the presentation appears to endorse the “Weight Inclusive” approach to medical care, including the statement that “Health and well-being are achievable for all regardless of weight.”

It’s hard to believe that this is a genuine claim taught to future physicians at a medical school, but nevertheless it appears in the presentation.

To be clear, excess weight and obesity are strongly correlated with elevated mortality, with severe obesity potentially shortening life expectancy by up to 14 years. In many circumstances, properly selected patients with obesity who lose significant amounts of weight have been shown to live longer, with better quality of life.

In addition to neglecting the wealth of evidence on the health risks and preventability of obesity, which make it highly irresponsible for a presentation at a medical school, the presentation’s claims are tinged with an ideological flavor.

“This course will make Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and other wealthy corporations very happy. So-called ‘fatphobia’ is ideologically driven science denial, specifically, denial of the adverse population-wide health effects of obesity,” said Kevin Jon Williams, MD, Professor of Cardiovascular Sciences and Professor of Medicine at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine. “We’re not talking about aesthetics, which change from year to year and culture to culture. Obesity makes people sick, shortens lives, and impairs quality of life.”

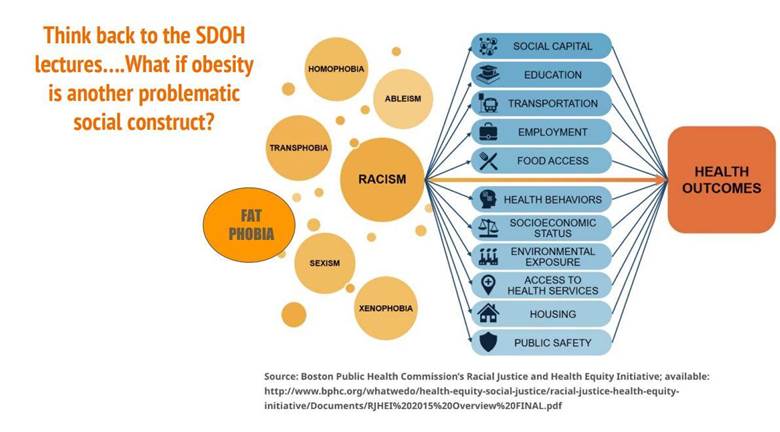

Several slides invoke concepts such as “social determinants of health” or SDOH and “implicit bias.”

For instance, the presentation dares to ask the question: “What if obesity is another problematic social construct?”

This framing obfuscates the empirical, physiological realities that obese people face, such as elevated mortality. Is heart disease a “social construct” as well?

Moreover, the presentation references social determinants of health (SDOH), which are social, economic, and environmental conditions that associate with individuals’ health. But associations do not prove causality.

The role that these so-called “determinants” actually play in determining health outcomes is not well supported.

Although SDOH may be correlated with disparities in health outcomes, the evidence that SDOH actually cause poor health outcomes is shoddy and weak, at best.

Much of the scholarship on the topic confuses social and economic conditions that correlate with poor health outcomes with the actual causes of those outcomes, ignoring other factors such as individual agency and health decisions that contribute to health outcomes. For example, despite its financial cost, smoking is more common among poor people and explains “much of the disparity in health outcomes.”

Unlike targeted interventions to improve obesity, high cholesterol, or high blood pressure, targeted interventions to improve SDOH have a poor record. To date, no study has been able to show that the introduction of a full-service supermarket in a so-called “food desert” lowers the body mass index (BMI) of nearby residents. Programs in 19 counties in Texas and Illinois addressed income disparities by establishing a Universal Basic Income (UBI). But recipients of UBI “reported no increase in access to or utilization of health care.” UBI did not lead to lasting “physical or mental health improvements,” and “recipients were four percentage points more likely to report a disability or health problem that limits the work they can do.”

In other words, SDOH have not been shown to “determine” outcomes, as the name implies; the more apt and accurate description would be “Social Associations of Health (SAOH).”

As another example of ideology over science, the presentation on obesity urged medical students in the audience to take an “Implicit Association Test” to evaluate their own biases toward overweight people.

Yet the notion that Implicit Association Tests predict real-world behavior is dubious: these tests fail to meet widely-accepted standards of reliability and validity. A lay summary of the problems with Implicit Association Tests can be found here.

Moreover, a 2013 meta-analysis published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that Implicit Association Tests were “poor predictors” of real-world bias and discrimination.

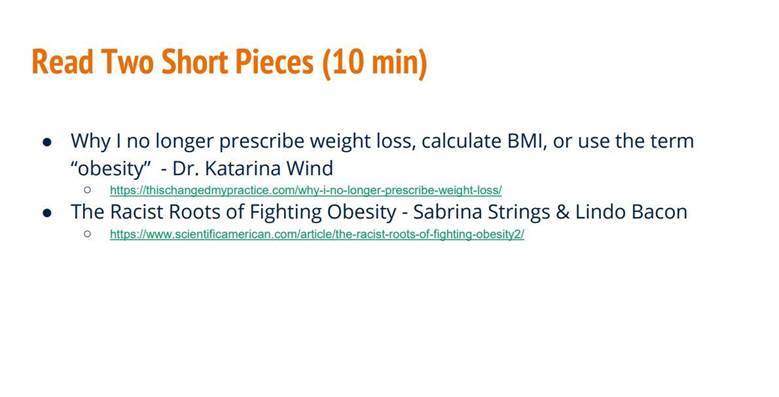

In another slide, the presentation on obesity recommends that the future physicians read two articles, including one titled “The Racist Roots of Fighting Obesity.”

That latter article argues, among other things, that many health concerns typically associated with obesity are in fact attributable to weight stigma – which, in the case of black women, is racially charged.

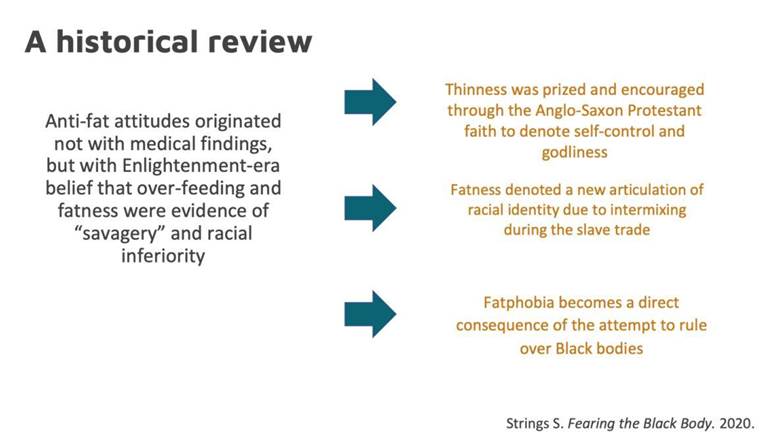

The presentation links “anti-fat attitudes” to racism, slavery, and the “Anglo-Saxon Protestant faith,” arguing that “fatphobia” is a “direct consequence of the attempt to rule over Black bodies.” The notion that “fatphobia” is a consequence of the slave trade, while slavery itself is a practice that has occurred across various ethnic groups and nations since the dawn of humanity, is dubious to say the least. Moreover, singling out an ethnicity and a branch of Christianity for this harsh criticism is historically inaccurate, possibly biased, and may engender ethnic and religious biases in these students.

Of course, it’s unclear how, exactly, these claims alter the reality that obesity poses health risks. And it’s exactly this reality that needs to be taught to medical students so that they can better care for their patients.

The presentation concludes with slides urging students to adopt weight-inclusive practices going forward, including a suggestion that they do not “blame” patients for their weight-related condition.

While physicians should not be cruel to their patients or belittle them, they likewise should not rob patients of their agency or their ability to change their health outcomes through personal choice. Avoiding highly-processed foods, for instance, is just one example. Yet the slides encourage “Increasing nutrient dense foods”.

Simply put, this presentation is full of claims that are politically charged and irrelevant to the practice of medicine at best, and inaccurate and dangerous at worst. It also plays into the hands of wealthy junk food, beverage, and agricultural interests that push harmful highly processed energy-dense foods and drink.

“The anti-science ideology of ‘fatphobia’ seeks to deny our patients the benefits of lifestyle improvements, medicines, and surgery to improve their lives and quality of life,” said Dr. Williams. “It is damaging and wrong.”

The Lewis Katz School of Medicine should not seek to inculcate its students in ideologies that promote harmful, misleading claims.